Feature: Dipping‑Distance Tools: Sight, String, and Sea

2025-12-03

I recently roamed the Baltic coast, navigating from lighthouse to lighthouse, measuring dipping distances using a calculator and a compass.

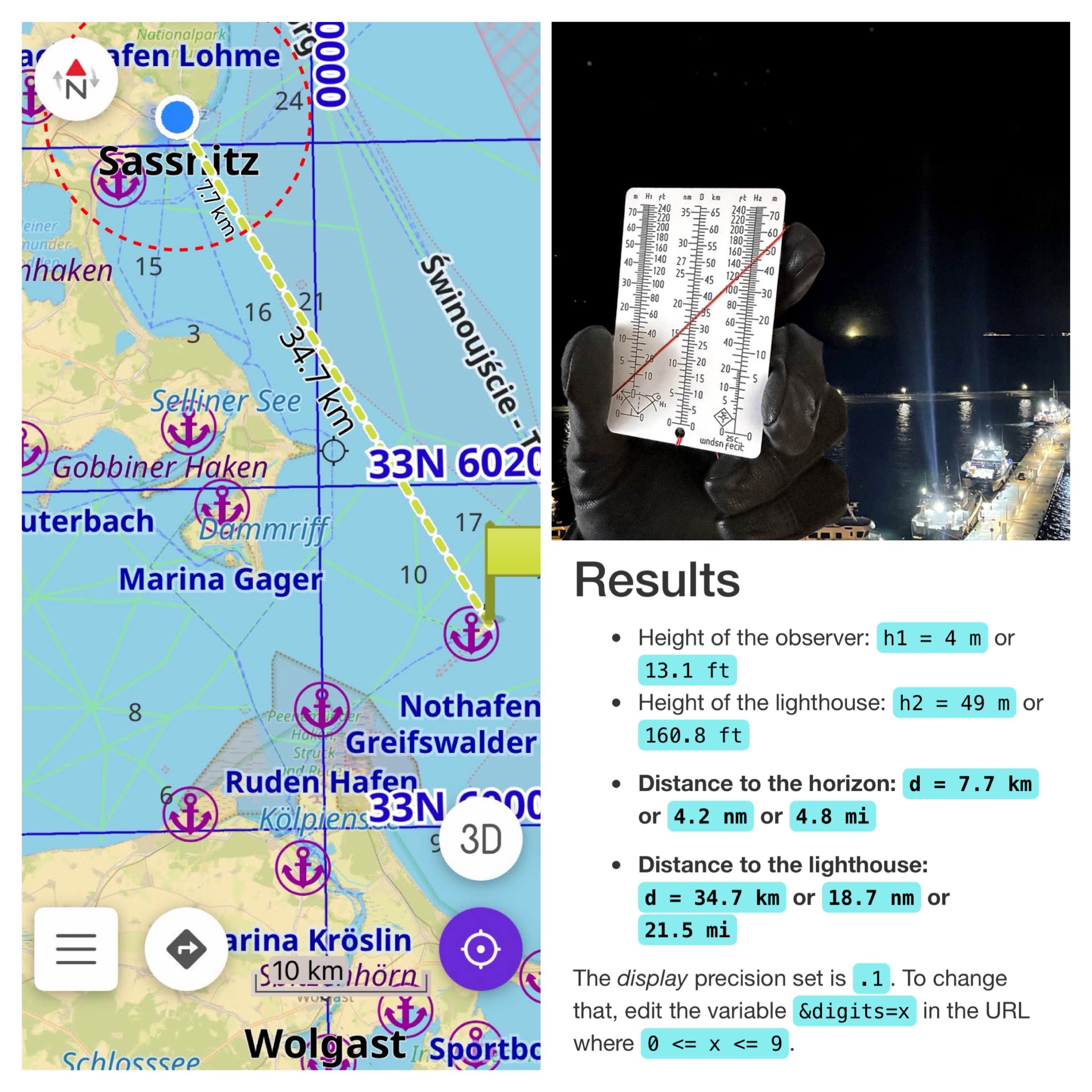

On the map on the left you see the distance from the vantage point to the lighthouse, at a distance of 34.7 km. Also note the dashed red circle at 7.7 km, marking the visible horizon. The far light at the center of the top-right photo shows the light of the lighthouse. The bottom right shows output from Tycho with the inputs from the observation.

I moved on the shore, along the coast, stepping up rocks and seawalls to set defined eye heights above sea level and to fix the position a distant lighthouse first resolved over the horizon. The operation was, as always, deliberately low‑tech. I relied on careful observation, repeated measurements, trust in basic geometry and a few square‑root calculations rather than sophisticated electronics, except for an electronic altimeter provided by my Garmin watch.

From fixed coastal vantage points the routine was straightforward and surprisingly repeatable. I would pick a charted lighthouse, measure and note my eye height above the waterline at the chosen shore position, and scan the horizon with the naked eye and at times, a monocular. Frequently the first hint of the light came not as a discrete point but as a faint loom, a diffuse sky‑glow that brightens the area just below the horizon. That loom gave an early indication but not a precise distance. The definitive moment was when the structure or the light itself resolved into a stable point: the instant the line of sight just cleared the Earth’s curvature. At that instant I recorded a compass bearing and I used the calculator to run the dipping‑distance arithmetic.

The underlying math is simple in form but sensitive in practice. Dipping distance depends on the square roots of the observer’s eye height and the lighthouse’s focal height; for operational use mariners multiply the sum of those roots by 2.08 to allow for typical atmospheric refraction:

distance in nautical miles = 2.08 · (√h1 + √h2)

Working from shore made the sensitivity to observer height easier to control than aboard a pitching boat: changes in platform elevation still altered the square‑root term enough to shift the predicted range by a measurable amount, but I could repeat positions and re‑measure more reliably on stable ground. Atmospheric clarity also had a tangible effect: haze and low contrast delayed the moment of clear sighting, translating into a difference of a few nautical miles versus very clear days. Tidal state in the Baltic was a smaller factor at some sites but was still noted,[1] since it changes the reference plane for both observer and light.

Repeating observations up and down the coastline made one operational limitation obvious: doing square roots and multiplications by hand while moving between sites is time‑consuming and invites error. A nomogram seemed the natural solution (I later learned that those already exist, in theory that is[2]). I translated the dipping formula, Wndsn-style, into an acrylic instrument so that when you align a string between observer height and lighthouse height the intersection point on the center scale gives distance directly in kilometers or nautical miles. The acrylic dipping distance calculator is instant, rugged and forgiving of the small motions and hasty timing of fieldwork. Two steps, align and read turn a fiddly calculation into an intuitive hand motion that works equally well on a cliff edge or a concrete pier. The nomogram can even be used to solve inverse problems: given a sighting and distance it can estimate the required observation height or the object’s height.

To complement the physical tool I built a Tycho web calculator implementing the same practical convention using the 2.08 multiplier that accommodates average refraction, accepting meters or feet and returning imperial miles, nautical miles, and kilometers. While the acrylic instrument excels for quick on‑site checks, the Tycho calculator is handy for pre‑survey planning, batch calculations, and saving and exporting data in different formats. Together they create a simple workflow: plan routes and sample heights with Tycho, verify alignment and range with the acrylic instrument on the shore, and confirm with a bearing and a recorded fix.

An additional useful capability is the simple horizon mode: setting the lighthouse height (h2) to zero on the nomogram or in Tycho returns the distance to the visible horizon for your current eye height. That distance is a neat, reproducible data point that can be plotted on a map as an interesting visualization: drawing a horizon circle from a cliff shows the area visible from that vantage point and becomes a compelling way to compare visibility envelopes between sites or to visualize how elevation and local topography alter how far can see out at sea.

The coastal excursions reinforced that simple, repeatable measurements from shore can be powerful. The acrylic instrument and the Tycho calculator grew from a practical need to reduce arithmetic in the field to make a dependable, low‑tech survey method out of basic geometric principles. The 2.08 factor proved useful under actual atmospheric conditions; the purely geometric constant would have underestimated visibility in most observations. Loom is a helpful cue but not a substitute for the precise position the object resolves. Because modest changes in observer elevation or atmospheric clarity produce nontrivial shifts in range, so careful recording of site conditions matters.

In the end, roaming the coast with only a few instruments proved once again the value of tools that are immediate and robust. The acrylic instrument puts a distance on a string in a single motion, and the web calculator offers planning and problem‑solving in planning and evaluation. Both emerged directly from repeated coastal observations and from the practical need to turn a visual event into a reliable navigation fix.

See also:

- The Dipping Distance Calculator in the Wndsn Store

- The Dipping Distance Calculator on Tycho

- The Navigation Primer Wndsn Mini-Course includes an exercise using dipping distance.

References:

- Every buoy has a website: Pegel Sassnitz. ↩

- Compare the Struysky diagram. ↩